Granny’s at Brinkhill – Chapter Two

Granny was an excellent cook. From her dark and mysterious dairy she produced meals of consistently high quality with perfect timing every day. This was vitally important to the men who’d been working in the fields since dawn and whose dinner break was only just long enough for them to eat and have a few minutes to relax before going back to work.

The meals were cooked on a huge black leaded range which had two boilers, at least one oven and various movable pieces of equipment attached to the ironmongery in front of the fire. These were used to support kettles and saucepans. The area in front of the range was Granny’s own territory; hers and hers alone. She was clearly something of an engineer as she fought that range every day. She kept the fire properly stoked in different areas to maintain a steady oven temperature. She ensured that there was a flat area for the steamer to sit. She pushed and pulled dampers, swinging the saucepans in and out so that the vegetables and the meat were ready together. I think that it would have been easier to drive the Flying Scotsman than to cook on Granny’s range but she did it.

She was a tiny thin woman and her handling of that mighty beast with all its hazards was a work of art. I was told that I must stay on the opposite side of the room, and behind the kitchen table, as it was dangerous to be near the range when Granny was cooking. I could see that it was and I never challenged that instruction. Grandad, Uncle Jack and sometimes Uncle Horace always arrived promptly for their dinner, at which point Granny handed over to Auntie Edith and Auntie Marjorie to dish up the food while she snatched a few minutes to sit in her rocking chair. Even then she seemed to be jumping up every few seconds to keep an eye on the suet pudding steaming on the fire, or to check on the pie in the oven.

The men were always served first. The women ate when the men had finished. This was for practical reasons. There was no time to spare. It was a quiet meal with no conversation; no time for that either. Auntie Edith hovered, there if needed.

The first course over, the pudding was produced. Granny’s suet puddings were featherlight and delicious and so was the pastry on her pies. I was brought to the table at this stage and my lemonade would appear as if by magic. I was always given half a glass and told to, “have a few sips now, and the rest as you eat your dinner.” I was then given my pudding. Yes, my pudding. Granny always gave me pudding first, meat course second. There was history here.

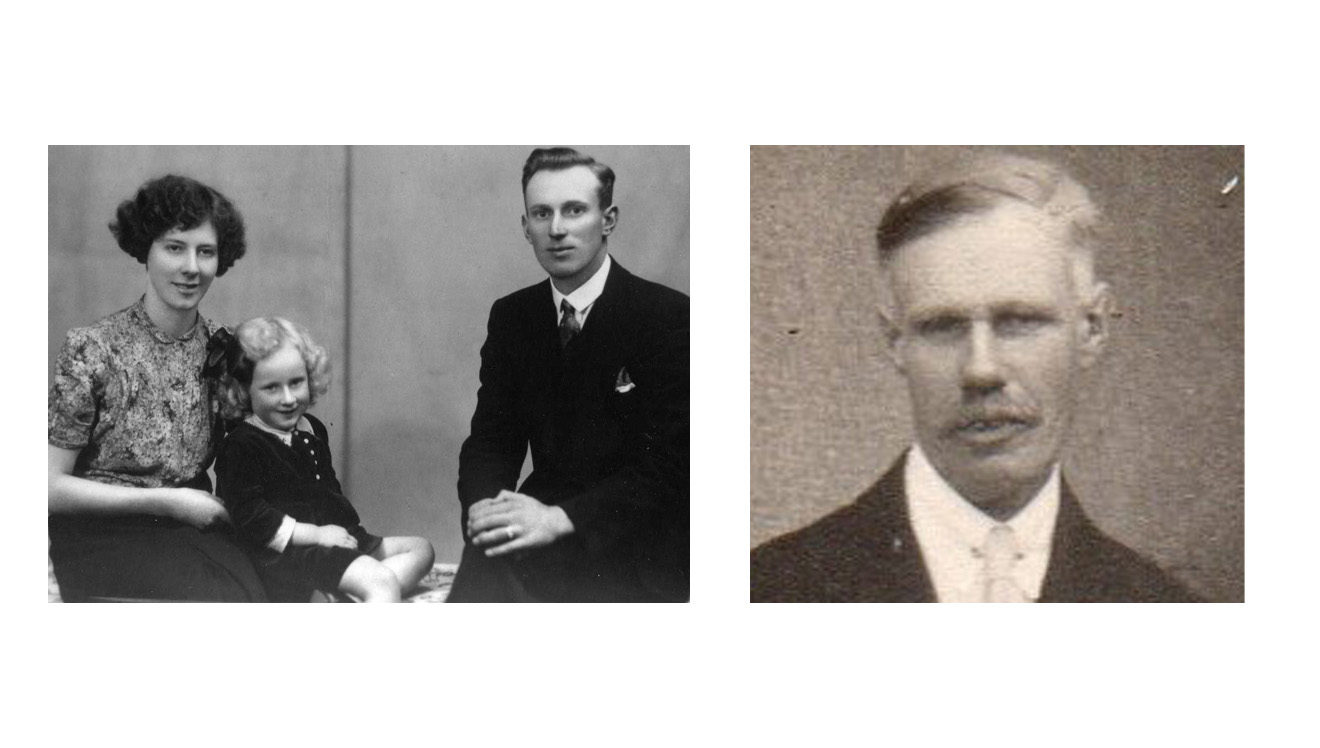

I was the first child of a young mother who was determined to do everything properly, as she saw it. My mother loved dairy products. She used to rhapsodise about drinking milk warm from the cow when she was a child. Milk puddings, custard, blancmanges and the like abounded in our house. I can remember liking milk and even once, as a toddler, reaching up and taking the milk jug off the table my mother was laying for tea and draining it. I was never sure if she was cross because I’d helped myself to the milk or because I’d drunk it out of the jug – probably both. My next memory of milk is that it started to make me physically ill. I was still a pre-schooler and milk was considered an important part of the diet for young children. Food was rationed and sometimes scarce in wartime and faddiness could not be tolerated. Attitudes to children were often quite Victorian, and onlookers were quick to decide that a child was ‘attention-seeking’ and ‘spoilt’. My poor mother, trying to deal with this sudden and – to her – incomprehensible change in my attitude to milk, did her best to persuade me to like it again by suggesting that I just have a sip, or a small spoonful of custard on my puddings. The resulting contamination gave me an aversion to the second part of a meal, even if I’d have liked the pudding by itself. My resistance to anything milky became a war zone.