Granny’s at Brinkhill – Chapter Eight

As I grew older, those day visits gradually became less frequent. I was studying hard and was the first – though not the last – in the family to go to university. Granny and Auntie Edith were there through it all, interested and encouraging from a distance, sending me books of stamps to remind me that a letter would be welcome.

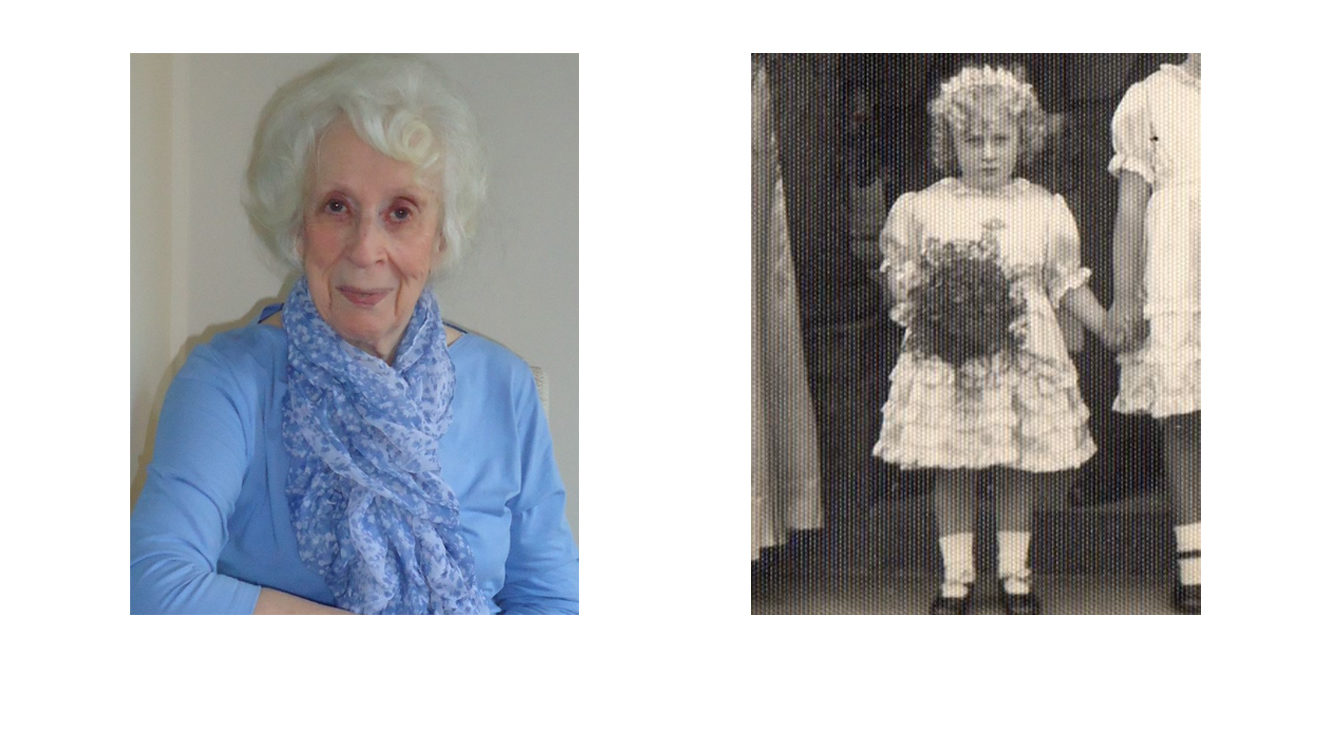

I think I had the best of Granny. By the time those post-war babies were old enough to go and stay with her as I’d done, she no longer had the energy to cope with the responsibility of a young child. My cousins remember her as a tired old lady, although I’m sure she cared about them just as she did about me. Weary as she may have been, her family was still of the greatest concern and importance to her and she kept in touch with everybody.

Helping her to keep her eye on the bit of her family with me in it was her right-hand woman, Auntie Edith. Like Martha in the Bible, Auntie Edith was ‘cumbered about with much serving’. As well as working hard with Granny all through the wartime and the difficult years that followed, she used to come to Louth every Saturday with lists of shopping to do for the family back in Brinkhill. Dad and I would meet her bus. Extricating her from it on those occasions when she had brought accumulators to be recharged was a complicated logistical exercise. These bits of equipment were needed to power the wireless, vital if you wanted to follow the news or enjoy some entertainment. They needed to be kept perfectly level to avoid spillage. Battery acid is nasty stuff. They were not really suitable for a bumpy bus ride. Auntie Edith sat with them between her feet and packed in around her were various bags and a suitcase. She wasn’t coming to stay – the bags and the suitcase were for taking home all the shopping she would do during the afternoon.

Dad would climb into the bus, unpeel her from all this baggage and disappear with the batteries to exchange them for fully charged ones. Auntie Edith and I would trundle off home with the bags and the suitcase where my mother had a meal waiting. Before we could eat, however, the suitcase had to be opened and the contents dealt with. This was always exciting. Granny found useful things to send to us all every week. I remember a jar of Uncle Horace’s honey, to be kept for the winter to soothe sore throats and other cold symptoms. There was often a rabbit, ready for skinning and cooking. Tucked away would be a packet of five Woodbine cigarettes for Dad who didn’t really smoke or approve of smoking as he said it was a waste of money, although I think he enjoyed Granny’s surreptitious offerings when he was working his allotment.