Farming Fit for the Future: Regeneration at South Ormsby

At South Ormsby Estate, we’ve committed ourselves to honouring our rural heritage while building for a better future where business, the community and the environment can thrive together. We passionately believe that protecting and enhancing both the local and global ecosystems on which we all depend must form the foundation of whatever future we build. With a new year upon us and climate change seldom far from the headlines, we’re taking the opportunity to outline exactly why our mission matters so much, and to deliver some good news on what we’ve achieved so far.

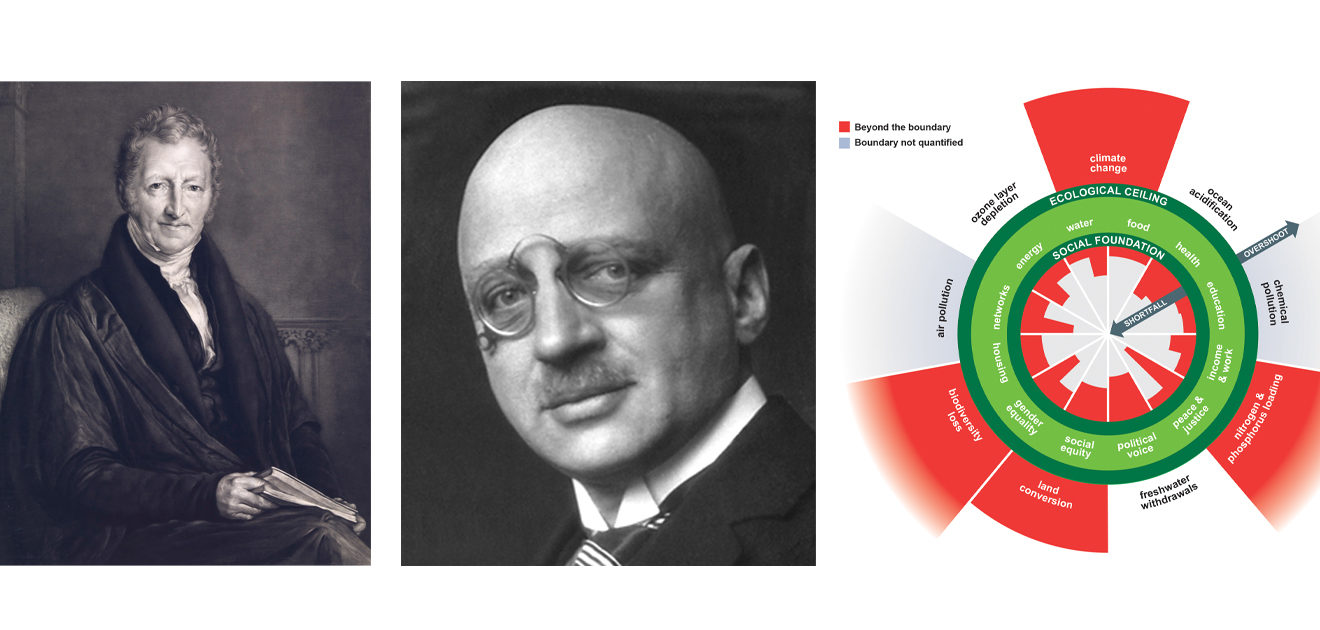

First, a little background. In the 20th century, human ingenuity ensured that farmers across the world could improve yields sufficiently to keep pace with booming populations. The Malthusian Trap – the idea proposed by English economist Thomas Malthus in 1798 that linear increases in food production will always be outpaced by exponential increases in human population – appeared to have been sidestepped. Momentous developments underpinned this, not least widescale mechanisation, efficient mass transport and the Haber-Bosch process by which nitrate fertilisation could be achieved synthetically. The Haber-Bosch process bears repeating as its results can’t be overstated; according to Carbon Brief, nitrate fertilisers were the dominant factor in allowing our planet’s population to surge from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 7.8 billion today.

It’s increasingly clear, however, that this model of farming comes at a cost that can’t be sustained indefinitely. In ‘A Life on Our Planet’, David Attenborough offers some thought-provoking statistics relating global population to atmospheric carbon and declining biodiversity over his lifetime:

1937: humans @ 2.3bn, carbon @ 280ppm, wilderness @ 66%

1968: humans @ 3.5bn, carbon @ 323ppm, wilderness @ 59%

1989: humans @ 5.1bn, carbon @ 353ppm, wilderness @ 49%

2020: humans @ 7.8bn, carbon @ 415ppm, wilderness @ 35%

It is widely appreciated that a healthy ecosystem at every scale is key to sustaining both agriculture and human health. This ecosystem is most visible when it takes the form of, say, charismatic raptors like buzzards and red kites riding the thermals overhead. Yet it is the invisible that matters most; the microscopic and invisible life beneath our wellies is the ultimate anchor for a food chain of which we are a part. A vibrant soil biome, teeming with an astonishing multitude of viral, bacterial and insect species, is simply indispensable if the soil is to support plant and animal life season after season while soaking up heavy rain and resisting wind erosion during droughts.

Unfortunately, intensive agriculture employing a full battery of fertilisers and pesticides can render soil toxic to its own microorganisms, less able to resist adverse weather and more likely to release rather than store carbon. Nitrate run-off can also damage the fragile ecosystems of watercourses and estuaries, most visibly in the form of algal blooms. To add insult to injury, Carbon Brief estimates that the production of ammonia fertilisers accounts for 1% of global energy use and 1.4% of carbon emissions.