Granny’s at Brinkhill – Chapter One

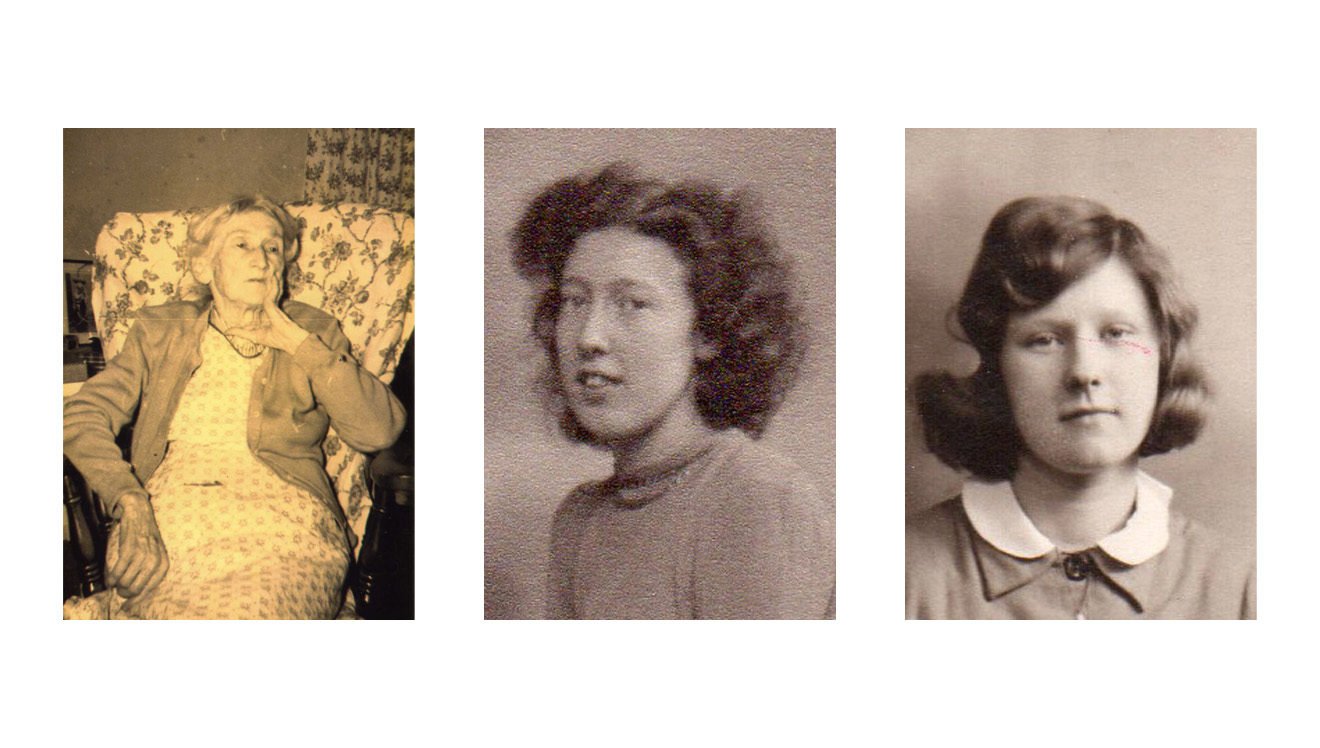

As a small child, Cecile Stevenson was the ‘littlest bridesmaid’ when Kath Brown married at South Ormsby Hall in October 1940. We’re delighted to bring you Cecile’s vibrant and poignant memoir of a 1940s childhood in the Lincolnshire Wolds, serialised in eight parts.

“We’re going to Granny’s at Brinkhill tomorrow and she says that you can stay for a few days.” With these words, my mother would have to deal with a child too excited to sleep.

This was the 1940s. The world was at war and life was restricted. A bus ride to visit relatives was an occasional treat, even if it was a recipe for travel sickness resulting from the spongy bounciness of the bus suspension, the passengers’ cigarette smoke and the ancient tobacco fumes buried in the uncut moquette seating. My mother always tutted in disgust and hid her nose in her handkerchief as she got into the bus. I was glad if we could sit near an open window but the pungent atmosphere and the prickliness of the upholstery on my bare legs were in their own way part of the excitement.

The bus from Louth to Granny’s started in Mercer Row and lumbered its way up Upgate, an accurately but unimaginatively named long hill which seemed to me to go on forever. At the top of the hill was a bungalow with a very unusual tree in the garden. The trunk was tall and slim and bare of branches. It arched over the garden boundary towards the road and the foliage at the top was a perfectly shaped umbrella. It looked like something out of a fairy-tale and I thought it was magic.

When I saw it, I knew I was really on the way to Granny’s. From the umbrella tree onwards, the bus rattled and jolted its way over the rolling hills to Brinkhill, if I was lucky. If not, we would have to get off at South Ormsby and I would watch disconsolately as the bus turned towards Tetford and disappeared up yet another hill, leaving me to face what always seemed like a long hard trek to Brinkhill. Sometimes Auntie Marjorie would come on her bicycle to meet us. She would perch me on the saddle and wheel me to Brinkhill, which was probably quicker and easier for everybody. I was not a happy walker.

Granny’s greeting was always the same – a long, drawn out mixture of ‘oh’, ‘ah’ and ‘aw’ which expressed pleasure at seeing me and incredulity at how much I had grown. I knew what she meant. We didn’t need words. Auntie Edith and my nearly-grown-up cousin Beryl were there too, smiling, busily making cups of tea and providing refreshments for the adults.

There was a ritual attached to my arrival for a holiday with Granny. Beryl was always given money and told to take me to buy a bottle of ‘pop’ from Mrs Humberstone who lived in a cottage along the road and sold soft drinks from crates stacked inside her front door. Mrs Humberstone was a tiny old lady swathed in black and she sat in her doorway waiting for customers. Cherryade and dandelion & burdock are the ones I remember but lemonade was my favourite.