Kilometres of Hedgerows & Centuries of Farming History

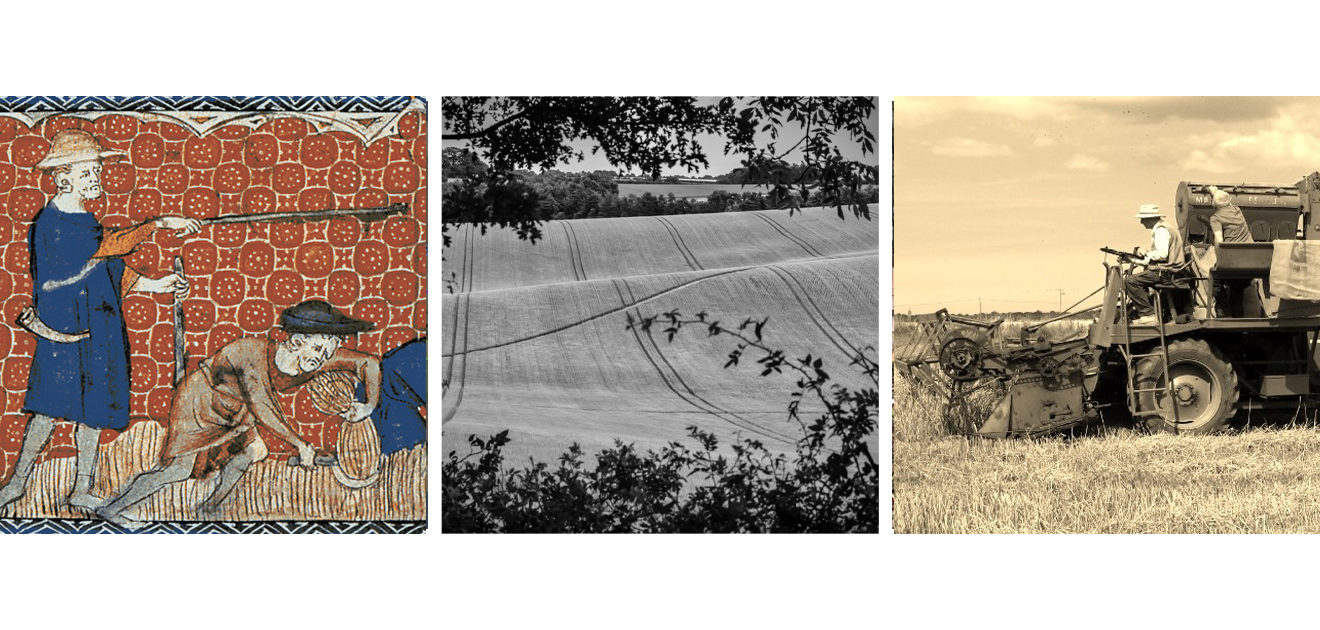

There’s a season for everything under the sun. Despite the sun’s present shyness, we’re about to jump into hedge-laying season. In 1888, South Ormsby Estate boasted 170 fields; this total had dropped to 96 by 2018, largely due to post-war farming priorities and the clearing of hedgerows. As we prepare to resume our ambitious re-planting programme, we take a look at how hedgerows fell in and out of favour over time, and why restoring them matters.

It’s thought that hedgerows were first planted systematically during the Bronze Age (c. 2,000BCE-700BCE). Elements of that ancient craft are still in use today and ‘plashers’ or traditional hedge-layers might argue that there’s little to improve upon. Plashing forms strong, long-lived and vibrant hedgerows that grow into impenetrable boundaries to livestock and oases for wildlife. Europe’s pre-historic settlers are thought to have plashed hedgerows to corral livestock after clearing woodland. The Roman legionaries who colonised Lincolnshire two millennia ago would have used plashing to reinforce timber forts and the craft would have been ancient even to them.

We’ve had the pleasure of seeing traditional hedge-layer Matthew Davey at work around the Estate. Matthew learned hedge-laying at agricultural college then gained experience on a countryside management project, learning traditional skills from older hands and securing his chainsaw ticket. Matthew’s job demands experience, skill and physical strength. No amount of theory is a match for laying kilometres of hedgerow year on year. In the Wolds, Matthew applies the Midlands style of plashing which includes binding the top of the hedge firmly with willow or hazel. Even if managed with a tractor and flail, modern hedges can become leggy and die out over time. By contrast, periodic plashing can extend a hedge’s life indefinitely and give wildlife a real boost.